Living with CLL

Select a country to see country specific content

Living with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

Experiencing a range of complex emotions such as shock, anxiety, anger, disbelief, and dejection when diagnosed with CLL is normal.[1] It is also normal to have questions and concerns. It’s important to feel as informed as you can about your condition and possible treatments, so you can decide with which you feel comfortable.

Remember to look after not just your physical, but also your mental health. Symptoms and the effects of treatment for CLL can have a huge impact on your everyday life. Your daily routine, socialising, and going to work may become difficult, which can take an emotional and mental toll. The fact that treatment for CLL commonly starts with a ‘watch and wait’ approach, could make you feel like not enough is being done and increase anxiety.

Try and talk to loved ones and be open about how you feel and how your diagnosis is affecting you. You can also confide in your doctor, who can advise you on patient support groups, trained counsellors, and social services, and explain your treatment plan to you in detail.

CLL affects your white blood cells, making you more susceptible to infections.[2] Wash your hands regularly, ask your doctor about vaccinations that can protect you, and take as many preventive steps as you can to avoid infection.

Treatment can also leave you feeling tired and nauseous.[2] Try to stay active and eat a well-balanced, healthy diet to keep up your strength and prevent weight loss.

Staying healthy through diet and nutrition[3]

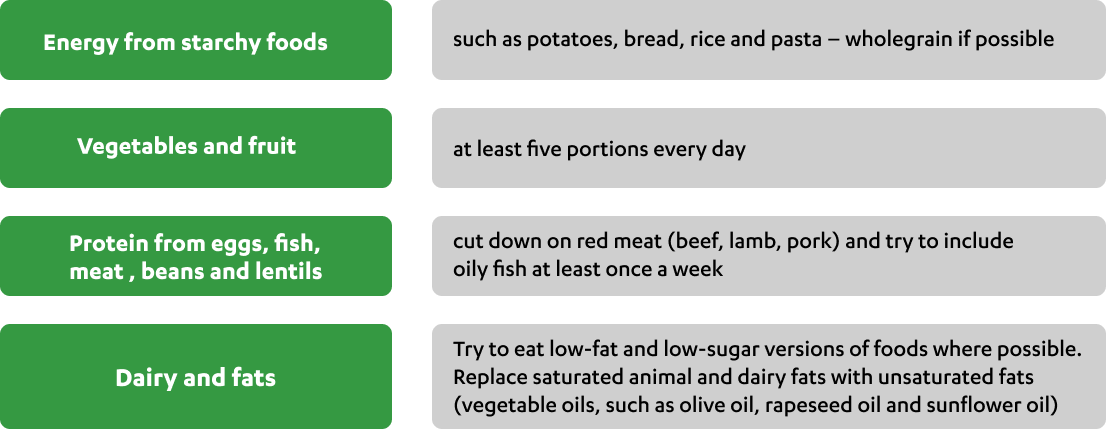

A healthy well-balanced diet is one step towards looking after yourself and coping with CLL and any treatment you have. Eat right and nourish yourself - if you can’t face big meals, try eating small meals more frequently, or try nourishing drinks, which boost your energy intake and supplement meals when eating becomes difficult or your appetite is low. If you’re concerned about your weight, your doctor can give you advice and support. The guidelines for a healthy diet are the same in CLL as they are for everyone:

Speak to your doctor or a dietician for specific advice.

General guidelines for a healthy diet

Drink plenty of fluids

It is important to drink enough fluids – at least 1,200 mL per day. This is 6–8 large glasses or mugs of fluid. This doesn’t have to be water – any sugar-free liquid will do, including tea, coffee and milk.

Alcohol

Avoiding alcohol or keeping it to a minimum can help you with managing fatigue. The WHO identifies alcohol consumption as a public health priority because of the impact on health.[4] Liver problems, high blood pressure, increased risk of various cancers and heart attack are some of the detrimental effects of regularly drinking more than the recommended levels.[5] Alcohol is also high in calories and can contribute to weight gain.

Reduce your salt and sugar intake

Whilst salt and sugar can make food taste great, consuming too much of either is can be bad for your health.Too much salt can lead to high blood pressure, which increases the risk of developing heart disease and having a stroke. The recommended level of salt for an adult is no more than 6g per day. Most of the salt we eat is ‘hidden’ in processed foods and snack foods that are pre-prepared such as crisps, cereals, bread, burgers, and ready-made meals including sauces and dressings.[6]

Eating too many products that contain refined sugar, which are usually high in calories and low in other nutrients.[3] This can contribute to weight gain and dental problems. Diets high in sugar also increase the risk of diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. You should try to avoid food or drink with refined sugar such as sweets, cakes, biscuits, and soft drinks. You can also opt for low-sugar varieties of jam, sauces, and dressings.

Weight loss

Sometimes people with CLL struggle to keep their weight steady. If you are losing too much weight, you may need to increase your calorie intake. This is not always easy if your appetite is not that good. It is best to talk to your doctor or nurse, and preferably a dietitian to get advice tailored to you.

Mental health

Feeling overwhelmed is a common response to a cancer diagnosis, and one which can lead to further feelings of anxiety and depression. It is important to remember, you are not alone in these feelings.[1]

Some treatments can exacerbate these feelings, as can the need to make treatment choices, finding time and money for care and general living, and communicating with family about your diagnosis.

Maintaining a strong support system – talking to your friends, family, colleagues about your CLL, your treatment and how they can support you will help you develop a support network. You may also wish to contact CLL patient support groups or online support communities.

Talking about how you feel

Speaking with friends or family about how you are feeling can help you reduce your feelings of stress, as it will allow them to gain a better understanding about what you are going through, enabling them to support you in the best way possible.

You may, however, find it difficult to speak to family and friends about what you are going through, which is where support groups can be useful as you can connect to people who are going through similar experiences to yourself.

A counsellor or therapist is another resource where you can explore your worries and feelings without the fear of being judged.

Your care teams

Whilst not everyone will need treatment from the start, your concerns and worries about treatment can still be there and are just as valid. Talking to your care team about these can help alleviate any worries and they can help signpost you in the direction of groups and resources that might help you.

Well-being

As well as ensuring that you are eating well and taking time to discuss your feelings about your diagnosis and treatments, it is important that you stay active regularly (if you can), take time to relax and get enough rest, as it will benefit your overall physical and mental wellness. Your condition may increase your chance of developing infections, so to help support your body’s immune system by eating a healthy, balanced diet, and try to avoid participating in activities where there are large groups of people. Below are some suggestions:

Staying active and setting reasonable goals – setting yourself realistic goals can help maintain a sense of accomplishment and a sense of purpose.

Find some activities you enjoy - for example light exercise can help reduce the symptoms of fatigue. Remember to talk to your health care team before starting any new physical activity routine, however, if you are able to stay active regularly it can help you manage your stress by boosting your mood. It can also:[7]

- Lessen depression and anxiety

- Help you maintain independence

- Reduce nausea and fatigue

- Reduce treatment side-effects

.jpg?width=616&height=286&format=jpg&quality=50)

Try to put dedicated time for yourself aside to do things for you. Sometimes it can be tempting to focus on what you should be doing rather than doing something you enjoy.

Finding time to relax doing an existing hobby (or take up a new one), for example, could help reduce your anxiety and stress levels, as it will focus your mind on something else and allows you time to process.

You could also reward yourself for completing you goals: go to lunch, meet a friend or cooking something special.

Thinking of traveling? You can talk to your health care team about your plans. They will be able to advise you if you need to take any special precautions (for example, against diarrhoea or coping with hot climates). They can also give you practical information and tell you where to find local sources of help for any unexpected medical emergencies.

References